A question I get asked regularly is why I’ve chosen to live in a van. The answer lies somewhere between choice and necessity. Mainly, this is a choice because I know of no other way that I could live with this relative freedom to park up in many natural, wild spaces and get the immersion in nature that I feel I need as a vital part of my life. In a smaller part, it’s necessity, because I haven’t found a way of earning enough money- that doesn’t feel destructive to the planet and that is also healthy for me- to buy a piece of land to live this low impact life in one place. In some ways this is the dream of rooting myself in the rhythm of one place, to get to know it intimately and it me. But the current (and numerous) obstacles to owning land in the UK make me think this is a dream that will not be realised.

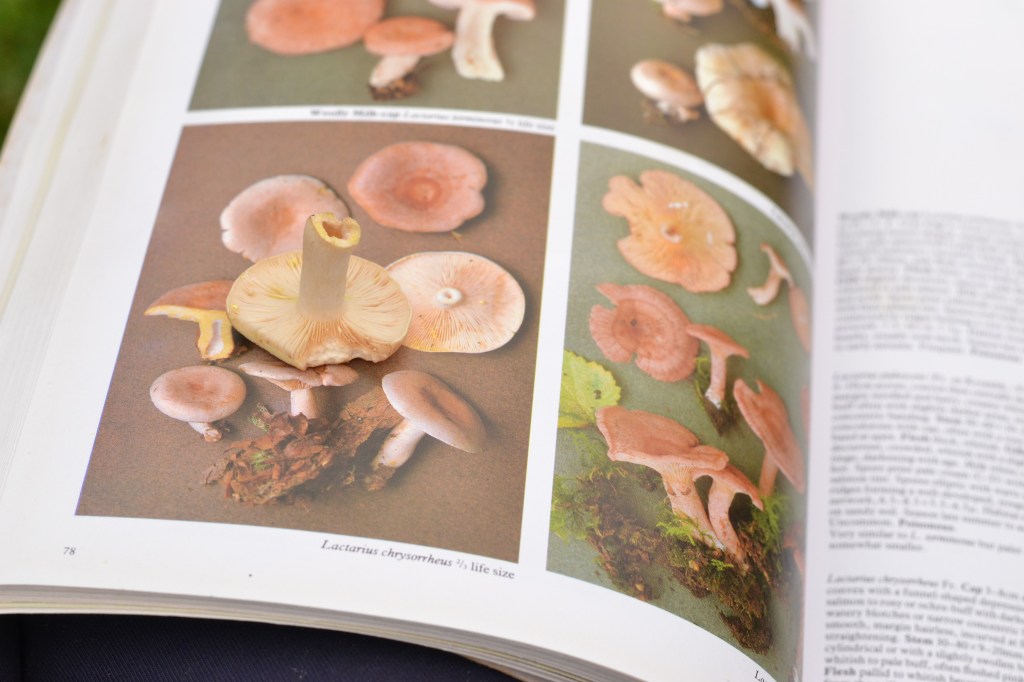

And right now that feels ok because I have found many ways of creating a connected and rich life while not being rooted in one place. Some of these practices are simple- sitting silently and observing, listening to the sounds of a place, walking barefoot. I also love to forage and I often remember places I stay because of something I foraged there; greens, berries, firewood. I now have a mental map of the places I’ve been, based on the things I’ve gathered there.

I can’t say it’s easy living in this way. There is nothing particularly convenient about it. But I’ve discovered that I like to challenge myself with finding resourceful and low-impact ways of doing things. With limited space, everything has to earn its place, so I love to find multiple functions for one object; my cajon is also a table, a stool, and a laundry basket.

I’ve realised that modern ways of living, though seemingly convenient, actually have complexity behind them and a certain way of tethering and limiting us. I don’t have a fridge, so keeping food cool is obviously tricky. If I did have a fridge, I’d need a more sophisticated power set up and I’d probably have to spend time on sites charging up. That would mean more expense, more technology to maintain, more emissions. That could be limiting for me in terms of finances and freedom. My ways around it are to eat less foods that need refrigeration, or to use a stream or river to keep things cool. (Making ghee out of butter which lasts a couple of months unrefrigerated means I can have some little luxuries!)

On the whole, not having a fridge is a sacrifice I’ve found to be worth making, and doesn’t feel at all limiting, if anything it feels more freeing. My diet could be considered to be basic, but I eat far less processed ‘convenience’ food and I think carefully about what I really need to eat. I also forage more, so possibly I get more varied microbes and micro-nutrients into my gut ecosystem than if I didn’t eat wild food (there’s currently a controlled study into wild foods and how they affect the human gut microbiome, The Wild Biome Project discussed on The Food Programme: Eating Wild on BBC Radio 4). In short, I feel healthier than when I do spend time in houses and around modern conveniences.

Space to wonder

But, let me be clear, this isn’t an Instagram lifestyle. For one thing, I shit in a bucket. And my van is of an age where she constantly needs care and repair. It is challenging. Sometimes it’s really rubbish. When your van breaks down in the middle of nowhere and you’re precariously parked in a layby, or the rain is incessant and you have condensation on every surface, not to mention moss growing on your window sills, you just wish you had a cosy, dry home to go back to. And sometimes I just don’t want to have to move on, I want to be able to say, This is where I live. Here.

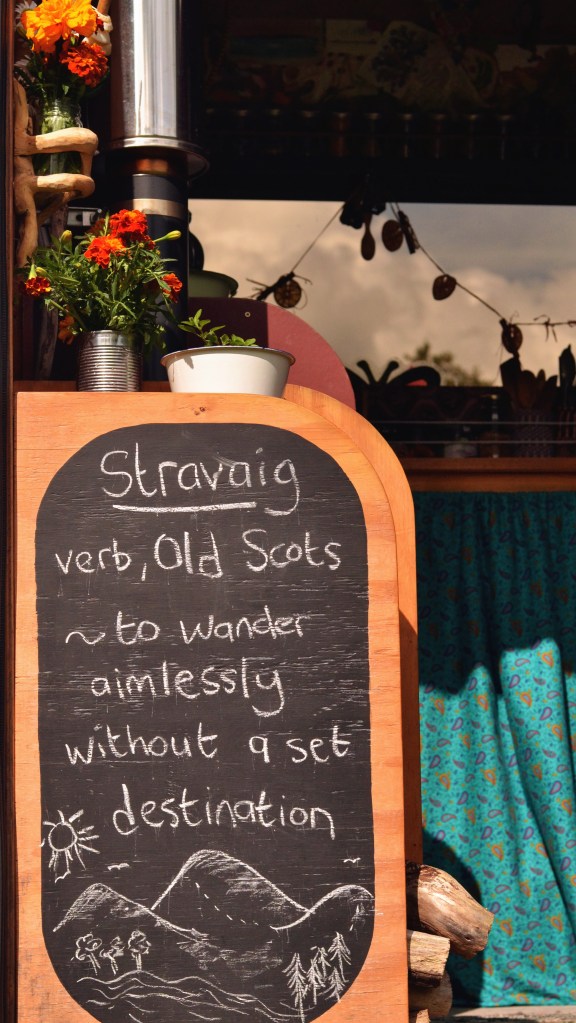

But living in this way I feel like I’m learning every day. No two days are the same. Generally the people I meet when I’m travelling are friendly, kind and interested. When they’re on holiday or travelling, they seem to be more open and curious, and so am I. It’s as though people have stepped out of their normal lives for a while and there’s space. That’s what it feels like to live in this way; no plans or routines, space and time to wander and wonder. There’s a richness in this life that no money can buy. I’ve met some wonderful people who are now dear friends, and this is one reason I carry on doing it.

There may or may not come a day when I feel that this isn’t the way I want to live and I’m not thriving anymore but right now, despite the challenges, this is how I want to move in the world. There’s a freedom, a rich simplicity that I haven’t found through living any other way, and so I’ll continue to stravaig through life.

If you’d like to receive updates when I publish a new post to my journal, please enter your email below: