August and September are the months when my fungi field guides and foraging books make an appearance. I pore over them like a gripping novel. Each year I get to know a few more fungi, some tentatively, with plenty of cross-referencing for reassurance. It’s taken me years to build up the knowledge and experience to the stage where I can now confidently identify around ten edible types, and that for now, is plenty for me. Personally, foraging isn’t just about finding food anyway, it’s a lot deeper than that, something I’ll talk about in later posts.

On a recent foray in the woods, my edible finds were chanterelles, winter chanterelles, and terracotta hedgehogs (left to right in the top photo). Interestingly, the hedgehogs I found were quite small and had a little dimple, some even a small hollow in the centre of the cap, not a characteristic I’ve seen before in this fungi. I did a quick search on Galloway Wild Foods, a fantastic resource for foragers and particularly useful as I’m in the Dumfries and Galloway region, where Mark Williams describes that he’s also found a few specimens in various locations with the same feature. These may or may not be a species called depressed hedgehog (!), however this isn’t known to grow in the UK, and they may just be a variant of the terracotta variety. Either way, they are edible and tasty!

I also found an edible milk cap that I’ve never seen before, and managed to identify it as lactifluus volemus, sometimes known as the Weeping Milk Cap (the specimen I collected is pictured in my hand). It was quite stunning how profusely the milk exuded from the cap when I cut it. Although this is classed as an edible fungi, I’m just not there yet, especially since it smells like a rubbery old fish when it’s been collected (which apparently disappears on cooking)!

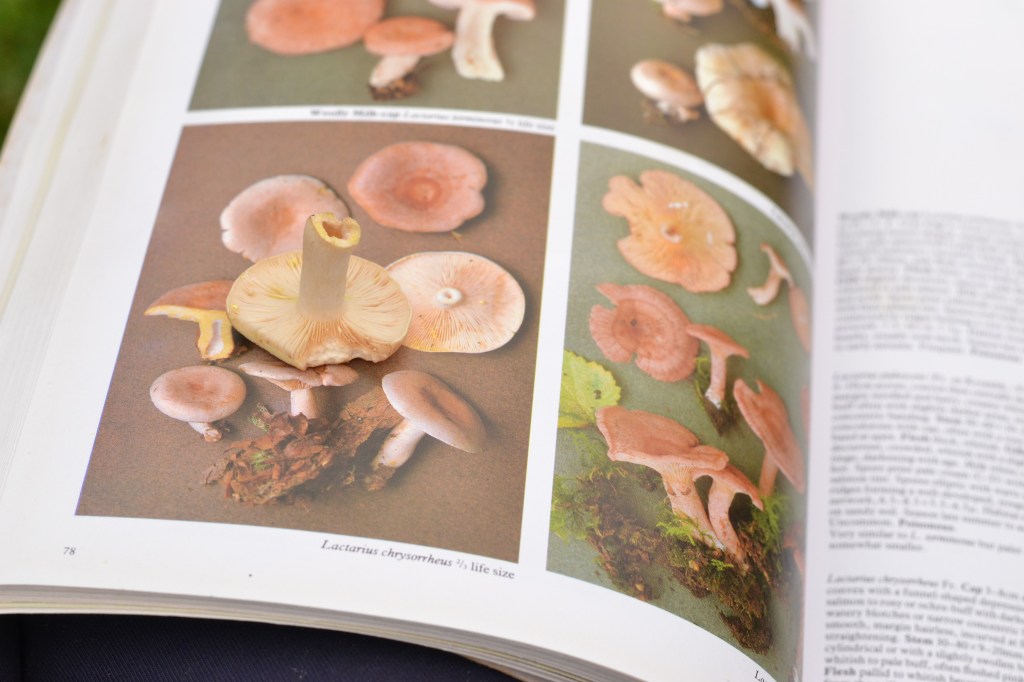

My non-edible find was another, smaller, milk cap that exudes white milk which turns yellow after a few seconds, a lactarius chrysorrheus (pictured resting on a page from the legendary fungi book by Roger Phillips, Mushrooms and other fungi of Great Britain and Europe).

This is just a few of the fungi I found on one three-hour foray, which covered a remarkably small area of ground. It’s a different way of moving when you’re looking for fungi; you can’t walk at a fast pace, you have to slow yourself down, observe the surroundings, and sink closer to the soil. You don’t follow the worn, linear paths, stomping and sweating; you take considerate steps into the brash and leaf litter, winding as you walk, stopping often to scan the ground. Crouching down to get a fox’s-eye view of the territory, allowing your eyes to adjust, the fungi realm reveals itself.

A wee disclaimer that this post is not intended as an identification guide. Please do your own extensive research and be absolutely sure of identification if you are planning to eat any wild fungi you collect.